As software created with Apache Spark grows in complexity, the “notebook-first” approach usually leads to what is known in software engineering as a “Big Ball of Mud”. The created notebook contains a monolithic application with evolutionary design. Logic is often implemented directly in notebook cells, components communicate with data frames that have implicit schemas, and testing becomes increasingly complex and slow.

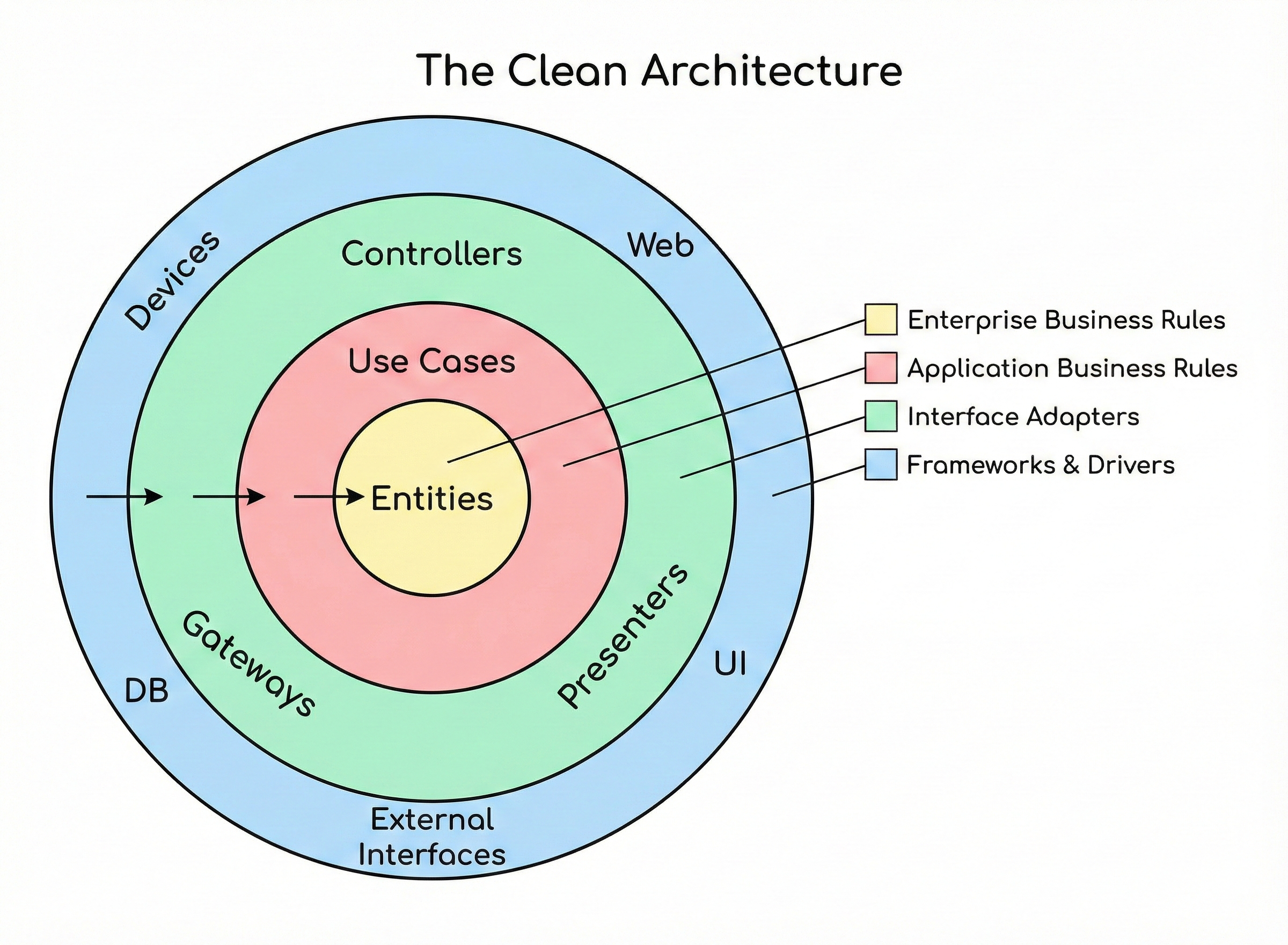

Applying Clean Architecture to Apache Spark development helps us solve these issues, despite the framework itself and underlying platforms (Databricks, Amazon EMR) not making the process any easier. The Clean Architecture enables building applications that are maintainable, testable, and independent of the external resources (databases, data formats).

The following blueprint helps to create a production-grade Spark architecture.

Entities

At the center of the architecture are the entities. In a standard Python application, these might be dataclasses; however, in Spark, these are all data frame objects with arbitrary columns and types. To provide type safety, we should avoid passing around generic pyspark.sql.DataFrame objects. The exceptional typedspark library makes the interfaces much more readable; it provides type checking, and as a bonus, autocompletion starts working in your IDE.

An example usage of the library:

class PersonSchema(Schema):

id: Annotated[Column[LongType], ExtendedColumnMeta(nullable=False)]

name: Annotated[Column[StringType], ExtendedColumnMeta(nullable=False)]

age: Annotated[Column[ByteType], ExtendedColumnMeta(nullable=False)]

wage: Annotated[Column[FloatType], ExtendedColumnMeta(nullable=True)]

Use Cases

The use case layer orchestrates the flow of data from and to the entities. It collects data using repositories, applies business rules, and prepares the result. This is where Clean Architecture really shines. We can test our business logic in isolation without the need to access external resources.

Some tips to avoid slow tests:

- Avoid I/O operations: Use in-memory fake repositories by returning synthetic datasets generated by

factory_boy. - Speed: Use single-node local Spark sessions to run the tests.

- Avoid unnecessary materialisation: Do not materialise temporary results so the Spark engine can optimise query plans efficiently.

An example use case with its corresponding test class:

class CalculateWage:

def __init__(self, spark_session: SparkSession, repository: AbstractRepository):

self._spark_session = spark_session

self._repository = repository

def execute(self) -> DataSet[PersonSchema]:

persons = self._repository.get_persons()

...

return persons

class TestCalculateWage:

def test_execute_calculates_wage(self, local_spark_session: SparkSession, person_model_factory: factory.Factory):

persons = person_model_factory.build_batch(...)

fake_repository = FakePersonsRepository(persons)

CalculateWage(local_spark_session, fake_repository).execute()

...

Controllers - Notebooks

These are the entrypoints in the application. What we need to strictly avoid is that the notebook becomes a God object. The notebook’s responsibility is to wire the components together, but nothing more.

- Initialise the infrastructure: Use the Builder pattern to create the

SparkSessionandDBUtils. They can be injected later into specific use cases when needed. - Inject external resource handlers: Instantiate the Repositories and pass them to the respective use cases. To remove the logic from notebooks entirely, consider using a dependency injection library.

Extract from a notebook code:

spark_session = get_spark_session()

repository = PersonsRepository(spark_session)

CalculateWage(spark_session, repository).execute()

...

External Interfaces

This layer is responsible for converting the outside world into a format that our application can work with. We use the Repository pattern here to abstract away the external resource. With that, you can separate the database layer, test the storage access independently, and switching to other technologies as the software changes remains simple.

Repository hierarchy with a fake class for testing purposes:

class AbstractRepository(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def get_persons(self) -> DataSet[PersonSchema]:

pass

class PersonsRepository(AbstractRepository):

def __init__(self, spark_session: SparkSession):

self._spark_session = spark_session

def get_persons(self) -> DataSet[PersonSchema]:

...

class FakePersonsRepository(AbstractRepository):

def __init__(self, persons: DataSet[PersonSchema]):

self._persons = persons

def get_persons(self) -> DataSet[PersonSchema]:

return self._persons

How do I start?

You don’t have to refactor your entire software overnight. Here is a step-by-step list to improve your architecture gradually:

- Pick one critical notebook that is currently difficult to debug.

- Extract the I/O logic into a separate Repository class.

- Define entities for your primary input and output DataFrames.

- Extract business logic from your notebook into well-sized use case classes until the notebook becomes free from logic.

Conclusion

Using Clean Architecture makes handling a Spark-based application much easier in the long run and transforms traditional “script-based” development into enterprise-grade software development.